Base camp

It’s amazing how alive the valley is at night in the summer. Thousands upon thousands of little critters emerge from every crack and crevice as soon as the sun goes down. The flow of ants and silverfish is endless, only punctuated by the occasional scorpion, toad, spider, rodent, or ring-tailed cat. Up on the western shoulder of El Capitan, the bustle of the valley is another world. Here the insects outnumber the people at least a million to one.

We settled down onto our sleeping pads in the least buggy clearing near the base of our route, too exhausted to mind the silverfish beneath us or the clouds of mosquitoes nipping at our faces. Had it been four or five trips up the approach trail to carry up our ten gallons of water, quadruple rack, aid gear, portaledge, sleeping bags, ropes, and pounds of food? We had lost count. By the time we started fixing the first pitches, we were already exhausted from shuttling loads up the slope in the 90 degree summer heat.

Despite the heat, the first pitches went smoothly enough. Pitch one goes free at a (sandbagged) 11b, but for us mere mortals it’s C2 hooking. I gave it to Chad, having climbed it once before (story for another day), but after 20 minutes of deliberation, he couldn’t get himself to stand up on the crux bat hook. I get it. It’s far from confidence inspiring. I took over the lead and made it up to the crux, a half-pad crimp at a 30 degree angle with just enough of an indent in one spot to get a bat hook to stay. I held my breath, unclipped my daisy from the bolt below, and stood up. It held. Two more steps up my aider and I was safely clipped to the next bolt where I could breathe again. The rest of the pitch went by without note.

Chad took the blank slab bolt ladder pitch 2, which by some miracle was freed by Tommy Caldwell at 5.13c. This pitch must have been bolted by someone the height of Hagrid because almost every bolt requires both top stepping and a cheater stick. Having climbed this one before too, I was happy to hand the lead over. It’s not hard, but damn is it annoying. I told him to skip the first anchor and go to the second anchor, but I also told him he only needed one piece of gear, a red camelot in a pod ⅔ of the way up. Turns out I was wrong, you need a couple more finger size pieces to get to the second anchors. With too little rope in the haul line left to shuttle up the gear, he had to downclimb back to the first anchors. Sorry buddy.

I paid the price for that mistake though. Pitch three is the famous window pane flake. From the first anchor you angle up and right until you’re in a steep left-facing flake. 30 feet up from the start of the flake, it cuts sharply back left another 30 feet. You aid by placing pieces deep in the flake above your head. As I climbed through, placing number one cams high above my head, silverfish showered down out of the crack above me. Literally hundreds of speckled gray critters flying out every time I stuck my hand in. An awkward position in the best of conditions, I tried to avoid getting these bugs in my mouth and eyes as I powered through.

The real punishment came at the end of the pitch though. After cutting right from the anchors to the flake and then sharply back left through the flake, you head straight up until you come to a bolt, which is your pendulum point across a wide section of blank rock. From the pendulum point, you swing another 30 feet to your left to access another crack system. At this point, I have two near 90-degree angles in my rope and it’s taking nearly all my energy just to pull rope out to aid up this crack. This part of the pitch goes free at a reasonable 5.9, but my attempts to free climb it were in vain. Resorting to more aid, I fought my way up to the belay.

We fixed our ropes to the anchors and with two 60 meter single line rappels, we were back on the ground. At this point, we have been baking in the sun for hours with little water after multiple trips up the slope on the western side of el cap. We were not so much exhausted as we are delirious. We set up “camp” as the last trickles of sunlight slip away.

Chad and I started climbing together in Washington DC. Well sort of together, we ran in the same circle, but never really roped up together. Once I gave him a belay up Montezuma’s Tower in the middle of a thunderstorm, but that was about it for our climbing partnership until he flew out to California to climb the Prow with me. It’s hard to find good big wall partners. Not only do they need to be competent enough to handle the fuckery that comes with big wall climbing, but also they need to be a decent enough person and easy enough to get along with that you can handle multiple days of hanging in a harness in deeply uncomfortable positions with them. Chad is that kind of climbing partner, the kind of person that you can have Blink-182 sing a longs with when things get extra fucked up.

The morning came and we picked silverfish and ants out of our beards, while chugging down cans of shitty iced coffee. We left our food and our real coffee sealed inside a canvas bag at the top of pitch three to keep it from the bears. Two 60 meter jugs and hauls and we were back at our high point. Quick but tiring when you haven’t ascended a fixed line in a couple years.

Back to our bag on the pitch three belay ledge, we noticed something was off. Our canvas food bag was unzipped and much of its contents were strewn around on the ledge. Fucking crows. We had noticed them hanging around the bag as we jugged up, but paid them little mind. The bag was thick enough to be peck resistant and the zipper was nice and hefty. Our bag was little match for the crows though who seemed to have no issue fully unzipping the bag. A quick inventory suggested that they only made it off with a few bars, a couple poptarts, and a bag of trail mix. We would later realize this was a grave miscalculation.

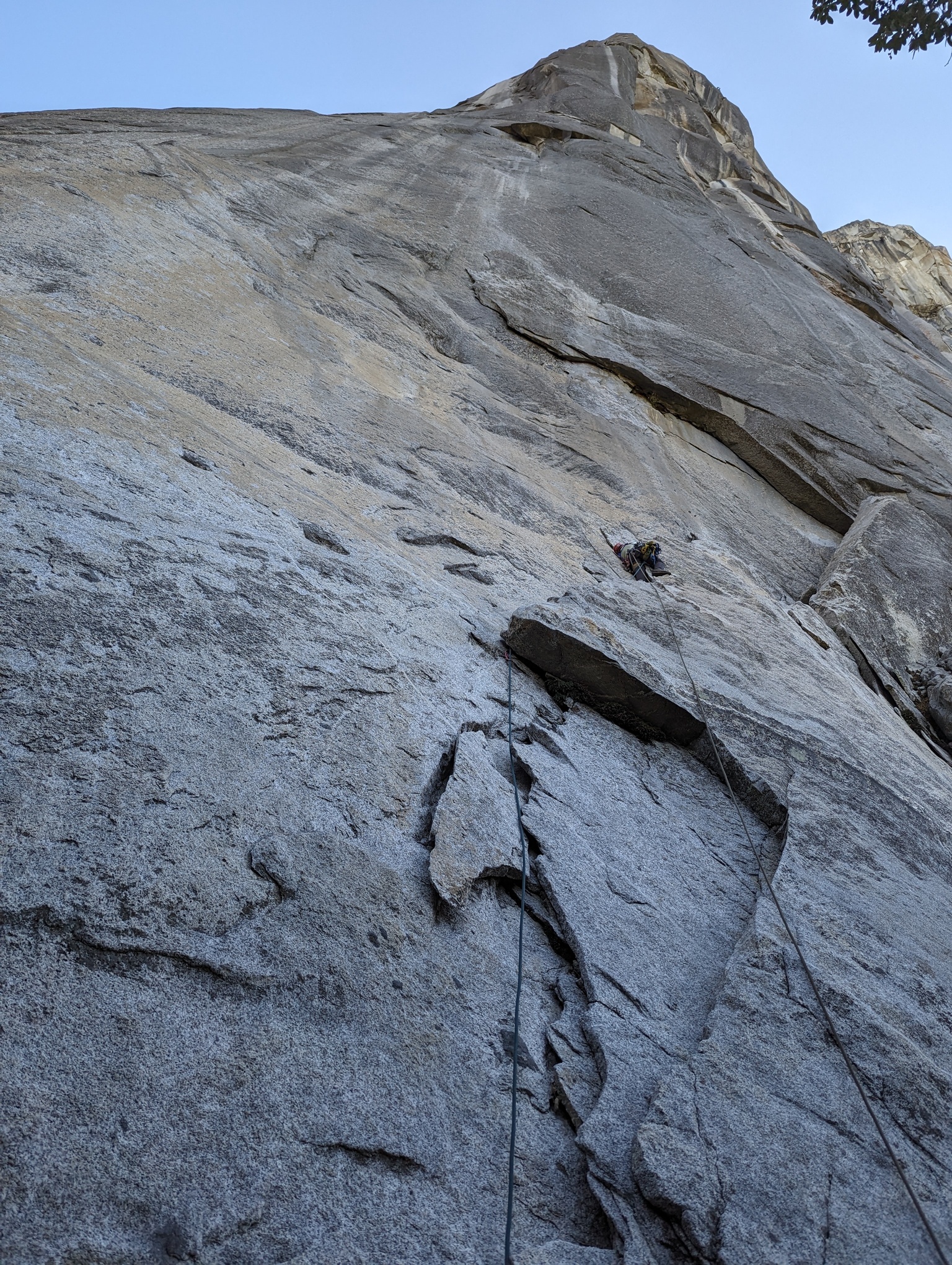

Pitch 4 past the hooking section

Pitch 4 was my lead. It starts on a beautiful face full of small edges taking you up to a series of C1 and C2 cracks. The first part is only supposed to go at 5.10, but it’s thin, requiring delicate edging. I opted for the hooking route, not wanting to slab climb with a haul line and aid rack hanging off me. One hook move was quite memorable. After standing up tall on the second from the top step, the next hook placement was still a ways out of reach. I down stepped one and bumped my left foot into the top step. The placement was still out of reach. I placed my other foot on the rock next to the hook and stood up tall when my daisy chain tugged the hook up and off the rock. All of a sudden, I was balancing on a single foot hold edging with my loosely tied approach shoe with nothing else keeping me on the wall. With the tips of my fingers, I got the next hook placed blindly and weighted it, holding my breath, my last piece of protection well below my feet. It held. I let out of a sigh of relief and kept climbing.

The biggest challenge of big wall climbing isn’t climbing. It isn’t pooping in a bag either. Hell it isn’t even hauling. It’s managing the damn belays. The ideal big wall anchor is three (or more) bolts, well spaced, with one higher than the other two. That way you can set up a couple slings or quads between the bolts with multiple attachment points for your two ropes, your haul point, your haul bag, your 700 cams, whatever else you dragged up with you, and your two climbers. Being able to spread out across three, four, or five master points lets you keep everything organized at your generally terrible hanging belay.

For some reason, the belays on Lurking Fear are only two bolts (fine, bolts are expensive and a pain to place) and are spaced not 6 inches from each other (why? God, why?). I am known for many things, but keeping a tidy and organized belay is not one of them. I can manage well enough and have improved over the years, but I am far from an expert, and these belays took me completely off guard. It was a comedy of dunces, a game of whack a mole. Every time I managed to un-fuck one part of the belay, another part would be a mess. Haul line wrapped around the haul bag? Lower down and un-fuck. Wait, now the lead line is somehow running through the straps of portaledge? Go in direct, untie, untangle, retie in. Wait now the haul line is tangled in the lead line. What the fuck am I doing? Can we just climb?

By the time I made it to the pitch 6 belay (two pitches shy of our modest goal of fixing pitch 8 and bivying on top of 7), the sun was already setting. Dehydrated, sore, and nearly delirious, I rejoiced. The anchor was three bolts. Three bolts! We could hang our ledge, our haul bag, and our gear with relative ease. It was a sign from the gods. We were meant to sleep here. I fixed the line for Chad and started the work of hauling our shit up. Chad got to the belay around the same time the bag did and we went about setting up camp. Finally we could relax, drink some much needed water, and dig into our dinners.

One problem though. Half of our dinner food was not in the haul bag. You see we planned one pack of pre-cooked rice and a couple of handfuls of dried beef sticks every night for dinner. We brought two pounds of dried beef for 4 days on the wall. That meant ¼ pound of beef each every night or 440 calories, 1.5 grams of sodium, and 48 grams of protein, everything we needed to recover enough to climb the next day. When the crow incident happened earlier that day, we didn’t even think to check if the 2 pound bag of beef sticks was still in the bag. Not only was it directly at the bottom, since we knew it would be dinner food, but it’s 2 pounds. How does a crow fly off with 2 pounds of food? Well google tells me crows have been seen carrying up to 2.4 pounds short distances, so I guess it managed to at least toss it off the ledge. So not only did the crows steal half our breakfasts and a chunk of our snacks, they stole the staple food of all our dinners. That and we were behind schedule.

A weird thing about climbing in Yosemite is that you have cell service. You can be having a mini epic high up on the wall and post about it on twitter if you really want to. Of course that also means you can get the weather report. When we left the ground, we had temps in the 80s on the valley floor and 20% chance of rain on one of our four projected wall days. With such balmy weather, we opted not to bother dragging up the rain fly, since its bulky and extra unnecessary weight. Given that, what we saw on weather.gov shocked us. 80-90% chance rain for two days straight, complete with thunderstorms and high winds.

So now, not only were we down half our food, but we were looking at two full days of soaking through our emergency bivy sacks and not climbing. Success was looking like little more than a pipe dream. As we were discussing our bail options though, we were surprised to see a headlamp rapidly approaching us on the pitch below. Nobody had been on the route beneath us all day. While I was leading up pitch 6, I noticed some people near the base, but assumed they were merely hauling up water and maybe fixing lines for the following day. As such, we were quite surprised when minutes later a head popped up and asked if he could clip our anchor.

“Wait did you start climbing tonight?”

“Yeah, we are short fixing and doing it in a single push.”

“How long ago did you start?”

“Maybe an hour and a half ago.”

They did in less than two hours what took us the better part of two days to complete, granted they weren’t hauling.

Our new friends lingered at our hanging camp just long enough to exchange some gear and share some beta for the pitches we had ahead of us. We were too ashamed to admit that we were already talking about bailing and the weather hadn’t even turned yet.

Once they were gone, we hatched our plan. Chad wanted to rap first thing in the morning, but I convinced him to take advantage of the weather window we still had to get a little higher up on the route. Pitch 10 and pitch 14 both had good bivy ledges that would allow us to gasp get out of our portaledge and walk around a tiny bit. The rain wasn’t due for another 36 hours, so we could climb another day, spend another night on the wall with a good camp, and then bail early the following morning before the rain hit us. Plus we still had a big bag of peanut butter M and Ms to work through.

We were up at dawn the following day. It’s hard to get a good night’s sleep on a portaledge. The middle sags ever so slightly, which means your lower back pain is waking you up every few hours. God forbid you need to pee in the middle of the night, then you’re trying to get out of the ledge without flipping it over on your partner who is sleeping next to you. Then you have to lower yourself down below the ledge with a grigri and pee away from the route. Add those things together and you’re pretty much awake once the sun hits you.

The best part of big wall climbing though is drinking coffee on a portaledge, half your body still inside your sleeping bag, feet hanging over the edge, watching first light hit the sheer cliff faces across the valley. Down below the road is so far away. The tourists are just starting to trickle in at dawn, but their presence is as insignificant as a dust mite crawling beneath your feet. The whistle of the wind overpowers any sounds you might hear from the ground beneath you. Up on the wall, 1000 feet above the valley floor, no one is around but you. It’s such a simple and beautiful feeling to be small, a speck on the walls of ancient stone.

Ledge camp

We savored the moment for as long as we could, but knew we had to start climbing before the heat of the afternoon if we were going to make any progress. Still dehydrated from the day before, struggling with our haul bags in the 80+ degree weather on the lower pitches, we were starting with a serious handicap. The pitch off our camp though is one of the best pitches of the route and I got to lead it. A 40 foot straight horizontal traverse on hooks and bolts with 1000 feet of air beneath you. I made my way out making sure to take the time to bask in the wild exposure. For the first time since we left the ground, the climbing felt like type one fun. It felt like exactly what I came up there for.

It didn’t last long though. Once I was through the traverse, I was groveling up a beautiful 5.9 splitter crack, fighting rope drag from the 90 degree turn in my rope, and lamenting my need to aid such a nice line.

Chad jugged up to the belay ledge looking as ragged as I had ever seen him.

“I can’t lead this next one. I’m wrecked.”

We had barely started climbing for the day and Chad already looked we had been at it for hours.

“I can lead it, but I need a breather after that haul.”

“I think we should go down. We are bailing anyway and I’m not sure I can climb much more today.”

The recommended amount of water on a big wall is a gallon per person per day. Maybe you can get away with 2 liters per person on a cool day. On a hot summer day, you probably want closer to 5 liters. Chad and I maybe drank 1.5 liters each the previous day, combined we drank less than a gallon. We were having such a nightmare at our belays, we didn’t want to dig into our haul bag for our water, so instead we just went without, a decision that we were now paying for.

The decision was made. Pitch 7 was going to be our high point. I couldn’t bring myself to rap just yet though, so we set up the portaledge and broke out our candy bag. For the next hour, we sat shirtless and shoeless on the portaledge, drinking water and stuffing our faces with as much candy as we could fit into our mouths (less weight for the descent). The sun had just hit us and we enjoyed the combination of the warm sun and the cool breeze reflected off the rock around us. While we weren’t going to summit, we could at least enjoy a little more of the best part of walling.

Around noon, we decided to pack it up and make the long trek down. The light breeze had turned to a heavy breeze and seven rappels with a haul bag is a solid day’s work in and of itself. Just as we stepped off the portaledge and into our aiders, the first heavy gust blew. The portaledge flew up in the air above our heads and then crashed down on us. We tried to grab hold of it and get it under control, but the wind would rip it out of our grasp, like trying to stop a sail boat from moving with your bare hands. Over and over again, the portaledge was ripped from our grasp. One person would manage to get a grip on one side, just for the other to lose it, and the ledge to twist around and fly away once more. We must have spent the better part of an hour wrestling with the portaledge before we could get it broken down and back in its bag.

You see the problem with rappelling down a traversing route is that you need to find a way to get back across the wall. You have two options: either you climb the pitch in reverse or you take a big swing and hope you catch the next set of anchors, a pendulum rappel. The preferred method generally is to go for the pendulum. Chad made the decision to bail, so he was stuck managing the haul bag, which is generally just a huge pain in the ass. As such though, it was my responsibility to manage the penji.

I lowered myself down about 50 meters from our anchor and tried to run against the wall towards the next anchor, some 40 feet to my left. To my dismay, the 40 mph gusts that were now blowing at a near constant frequency were pushing me back in the opposite direction. Dangling there, almost a thousand feet above the ground, the wind whipped me back and forth, into the wall, away from the wall, but always further away from my destination. 30 minutes went by, maybe longer. My legs were screaming at me from hanging in my harness in space. My feet were getting pins and needles from the circulation being cut off. No matter what I did, it seemed like the pendulum was impossible. I couldn’t get even 20 feet from the next rappel anchor. I resigned to my fate. I’d need to re-ascend the rope and then re-climb pitch 7 backwards.

Just as I fixed my prussick to my rappel strands though, a miracle happened. The wind stopped completely. Knowing my window was going to be slim, I ripped the prussick off and started running against the wall. First away from the anchor, then towards the anchor, then away from the anchor, and then towards the anchor, and then bam! The tips of my fingers just barely grazed the crack next to the anchor. I held on for dear life. With my other hand, I grabbed the crack and pulled myself in, then looped a finger through the bolt hanger, and used my other hand to clip my daisy chain. A wave of ecstatic relief, of elation crashed over me. The last crux was done. I pulled out my radio.

“I’m in. Finally. We are getting off this thing.”

Getting to the ground without summitting was bittersweet. We were happy to be safe and to be out of that windstorm that pounded us the entire descent, but so much work goes into walling. We spent three days hauling water and gear and fixing lines, for only one night on the wall. It was a shame, but still we were safe, out of the wind, with lessons learned, and about to eat a shit ton of pizza at Curry Village.

The next morning the rain started at 9am, 5 hours earlier than expected. It started nasty and continued on that way for two days. While we drove out of the valley, we knew that despite our misgivings, we made the right call. The big stone isn’t going anywhere and there are always more rocks to climb.